Contents

Overview and purpose

The purpose of this review was to identify and synthesise international and Australian evidence on interventions and approaches that have demonstrated impact on violence against women, to better understand: which conditions, processes and criteria support this impact; and how to combine interventions so that they mutually-reinforce each other for greater or broader impact.

The review gave particular attention to place and community-based approaches (see Glossary), and examined the elements and processes required to maximise their impact – especially those employing multiple components or strategies to harness a mutually-reinforcing effect. It was specifically concerned with interventions that demonstrated reductions in rates of perpetration and/or victimisation, while noting that other outcomes – especially reductions in the drivers and reinforcing factors of violence – are equally important and likely precursors to such impacts (footnote 1).

The review is part of a series of papers that will inform the inception stage of a multi-year project to develop a ‘saturation model’ for primary prevention of violence against women, led by the state-wide Victorian prevention agency, Respect Victoria. Respect Victoria describes a ‘saturation model’ as a method of implementation, coordination and evidence-building to strengthen multi-component prevention activity in a specific place and with defined communities. Building evidence for such a model is part of the agency’s commitment to identifying opportunities for scaling-up and systematising primary prevention initiatives (reference 28).

Background and context

Victoria is a world leader in settings-based prevention approaches to violence against women (footnote 2) (for example, through the education system, workplaces and local government), though the work is ‘as yet incomplete and has […] engaged a limited number of organisations and settings (references 29-30).’ Additionally, more than one hundred discrete initiatives have been funded under the Victorian Government’s Free from Violence strategy (reference 31), and innovative prevention approaches have been driven by, with and for Aboriginal communities, migrant and faith communities, women with disability, older people and LGBTIQ+ people (reference 29). An enabling policy environment and infrastructure in Victoria could potentially support, with adequate funding and appropriate design, piloting a place-based saturation model and its subsequent scale-up. In particular, it could provide a strong foundation for coordinated primary prevention activity at the regional level, as does the work of many local governments at the municipal level, and systems for collective impact exist in the state (reference 27).

Several Victorian-specific projects have also contributed to evidence on place-based prevention approaches, including the VicHealth-funded Generating Equality and Respect (GEAR) program, which tested a multi-setting, multi-strategy model for prevention of violence against women at a small-scale site. The three-and-a-half-year project highlighted the importance of building leadership, community readiness and infrastructure for prevention, and ‘built a transferable model for planning and leading site-based primary prevention activity (reference 32).’ An assessment of the impact of the GEAR program on the drivers of violence or levels of perpetration/victimisation was not possible at the time of its evaluation due to the short implementation timeframes. However, the evaluation report made several important recommendations, including the need for further investments in coordinated, multi-component place-based models, due to their strong potential to ‘affect attitudinal and behavioural change over time (reference 32).’

Lessons can also be drawn from the large number of process, output and outcome evaluations of the above activity, and other prevention work conducted to date. However, currently, there is limited evaluation and research evidence demonstrating the direct impact of Victorian prevention work on the severity and prevalence of perpetration or victimisation.

Globally, over the past decade, there has been a growing number of evaluations demonstrating that interventions designed to prevent violence against women can have measurable impacts. These impacts can be observed in relatively short timeframes and are not limited to reductions in the gendered drivers and reinforcing factors of violence against women, but also include significant reductions in perpetration and victimisation rates (footnote 3). Most of this evidence has been derived from evaluations of discrete projects or programs with a limited target population. This review sought, in the first instance, to learn what factors and conditions might have contributed to such impact to determine key lessons for Victorian prevention work.

However, to achieve impact across a broader population and sustain it over time, research indicates that small-scale and stand-alone interventions are not enough (references 2-4). Therefore, the review also sought to examine what international research and evidence tells us about combining and scaling interventions to measurably reduce and prevent violence at the population level, or about the conditions, factors, and processes that enable and sustain reductions.

Respect Victoria commissioned this review to address some of these critical ‘missing pieces’ in the evidence, as part of a series of papers that will inform the design, implementation and evaluation of a saturation model for Victoria.

Guiding questions

The following questions guided this review:

- What does recent research and practice tell us about the effectiveness of prevention interventions, in terms of impact on rates of perpetration and/or victimisation of violence against women?

- What do we know about the foundational conditions, variables or criteria that affect the extent of prevention practice impact?

- What do we know about how and whether outcomes from individual interventions are strengthened because of how they interact when coordinated with other interventions, and what design, implementation or contextual conditions contribute to any ‘mutually-reinforcing effect’?

Review scope

A focus on impact – at intervention level and population level

The review included studies on the impact of prevention work – with impact defined as reductions in victimisation and/or perpetration of violence against women – whether with specific intervention groups or at the population level (see Glossary definitions related to impact at different levels). It sought to identify conditions, criteria and processes that contribute to such impact, and/or to the mutually-reinforcing effect. In limiting its focus to the characteristics associated with impact, it did not seek to reproduce in detail all principles of good practice in design and implementation of prevention interventions (which are well-described elsewhere (reference 33)).

Specific attention to place-based approaches

While the review included a high-level scan of all types of prevention intervention (see Methodology), it gave particular attention to place- and community-based approaches employing multiple components (see definitions in the Glossary). Again, the focus was on factors affecting impact on rates of violence against women, rather than broader principles of effective place-based programming per se (reference 34).

Included studies from across low, middle and high-income contexts

The review’s scope was global. It included studies from low, middle and high-income countries internationally. As such it is distinct from, and complements, a forthcoming ANROWS review of interventions that focuses on high-income countries but includes a broader range of outcomes (i.e. beyond reductions in rates of perpetration/victimisation, the focus here) (reference 6).

Used specific definitions related to type of intervention

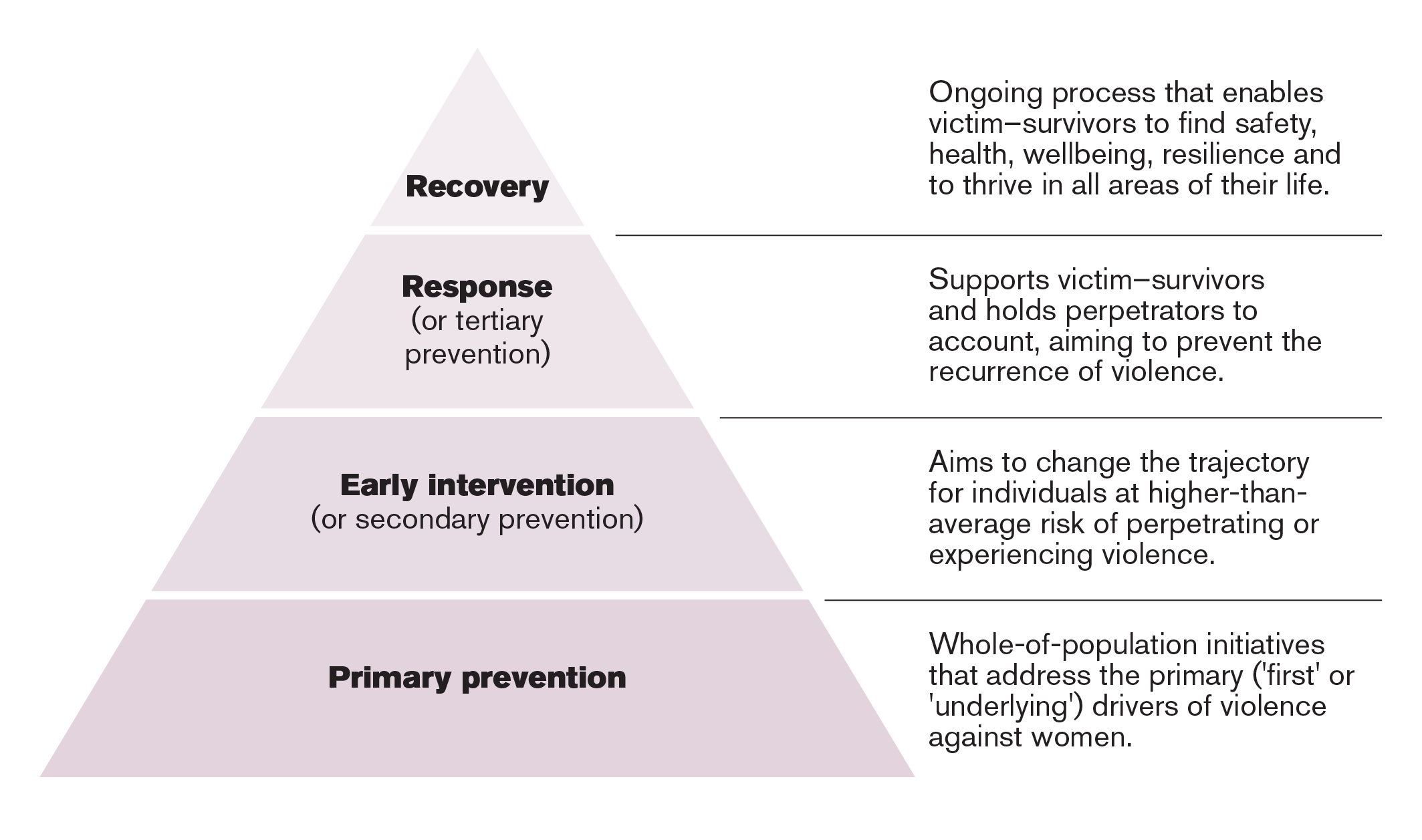

A range of definitions are employed in the international literature to describe different activity types to address violence against women, especially ‘primary prevention,’ ‘secondary prevention’ and ‘early intervention.’

This review uses the definitions in Change the Story (reference 4) (Figure 1 below), which are based on those outlined in the 2007 VicHealth framework for prevention of violence against women (reference 35), and later in the United Nation’s (UN) Framework to Underpin Action to Prevent Violence against Women (reference 36). Early intervention, and secondary prevention, is defined as activity with groups considered at higher-risk of perpetrating or experiencing violence, and primary prevention as whole-population activity addressing the (first/primary) drivers of violence. The definitions used in this review are guided by a socio-ecological model that entails changing conditions and environments (social, community, organisational) as well as working with individuals. Given the diversity of needs and experiences within any population, an intersectional approach, coupled with targeted work with specific population groups is a necessary feature of prevention work seeking to reach across a whole population.

Figure 1: Definitions used in this review

Included a range of interventions designed to prevent new violence, reduce recurring violence and/or reduce risk

The review was interested in how to lower the rates of violence against women, regardless of how source material described the type of interventions. That is, the review included studies of both ‘whole population’ interventions, and interventions with groups understood to be at higher risk of perpetration or victimisation. It also included interventions that demonstrated reductions in victimisation and/or perpetration regardless of whether these reductions were due to new incidents of violence being prevented among individuals not currently experiencing or perpetrating violence (i.e. compared to statistical expectations), and/or due to already existing patterns of violence being reduced or stopped.

Table 1: Types of intervention and impact in scope for this review

This table is based on UN Women (2015), p. 15.

In this table, the columns indicate the types of activities: primary prevention, early intervention, or response and recovery. The rows indicate the types of impact: preventing violence before it occurs, preventing recurring violence, and preventing long-term harm from violence.

| Primary prevention | Early intervention | Response and recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Focuses on the population as a whole, and the range of settings in which gender relations and violent behaviour are shaped, to address factors leading to or protecting against VAW. | Focuses on individuals and groups with a high risk of perpetrating/being a victim of VAW and the factors contributing to that risk. | Focuses on those affected by violence and on building systemic, organisational and community capacity to respond to them. |

| Preventing violence before it occurs | Build social structures, norms and practices that protect against VAW and/or reduce the risk of it occurring. (This type of intervention falls within the scope of this review.) | Mitigate the impact of prior exposure to risk factors and build protective factors. (This type of intervention falls within the scope of this review.) | Contribute to social norms against VAW by demonstrating accountability for violence and women’s right to remedy and support. |

| Preventing recurring violence | Build social structures, norms and practice that protect against and/or reduce the risk of recurring exposure to/perpetration of violence. (This type of intervention falls within the scope of this review.) | n/a | Provide remedy and support to women affected by violence and hold individual men using it accountable. In demonstrating this, it also strengthens social norms against VAW. |

| Preventing long-term harm from violence | Build social structures, norms and practices that maximise the prospects of rebuilding lives after violence, minimise its impacts and reduce the likelihood of recurrence in the longer term. | n/a | Support to individuals to prevent negative impacts of violence, promote rebuilding and reduce the likelihood of recurrence in the longer term. |

| Examples | Building women’s economic independence, while working with both men and women to strengthen equal and respectful relationships. Shifting norms toward gender relations and VAW through mutually reinforcing group education, community mobilisation and local media activities. | A psycho-educational programme for children who are exposed to parental violence to address the consequences of this exposure as a risk factor for future perpetration or victimisation. | A workplace policy to strengthen support for women workers affected by IPV (e.g. paid leave provisions, co-worker sensitivity training). Legislative and procedural reform to strengthen access to justice for victims of sexual assault. |

While very few studies on response or recovery interventions have been evaluated for impact on violence rates as defined here (given that is not the primary objective of such activity) (reference 19), they have been included with regard to their role in ‘mutual reinforcement’ of multi-component prevention efforts. That is, the review sought to understand whether combining interventions results in greater impact, and therefore looked not only at combinations of ‘all primary prevention’ activities, or ‘primary prevention plus early intervention’ activities, but also at a broader range of activity across the spectrum of primary prevention, early intervention, response and recovery.

Methodology

This review was a scoping study, seeking to identify and synthesise ‘relevant evidence that meets pre-determined inclusion criteria regarding the topic [including] multiple types of evidence [and aiming for a] comprehensive overview of the evidence rather than a quantitative or qualitative synthesis of data (reference 37).’ The findings presented provide a high-level overview of the state of the research and practice on the factors that influence the impact of prevention of violence against women interventions, with a particular emphasis on multi-component and place/community-based approaches.

The study parameters and inclusion criteria for resources were limited by the scope above and further refined through a process that included a high-level desk-based scan accompanied by discussions with Respect Victoria staff and several key informants. A deeper desk-review then mapped literature and practice on ‘combination’, ‘saturation’ or ‘mutually-reinforcing’ approaches to preventing violence against women, to understand what had been learned from these efforts so far. The review drew out key lessons from other place- or community-based programs employing multiple components, and possible directions for the design and development of a saturation model.

The review included primary research and evaluations, meta-analyses and evidence summaries, non-empirical evidence, and ‘grey’ literature on practice evidence, including that from broader areas of social change/justice and health promotion. A wide range of literature was sourced through the SmartCat academic search engine, supplemented by Google Scholar. The following search terms were used in a range of combinations:

- (effective) (primary) prevention / social norm change / social change / health promotion / public health

- violence against women / gender-based violence / sexual violence / intimate partner violence / domestic and family violence

- mutually-reinforcing / multi-component / saturation / scale/scaling/scale-up

- site-based / community-based / place-based / cohort

- intervention / program(me) (design) (standards) (principles) / model / framework / system / network.

Grey literature searches were undertaken via Google using similar terms as above as well as relevant online knowledge hubs and clearinghouses.

Over the past decade there has been a proliferation of literature in these areas, which has been comprehensively reviewed and synthesised in more recent years, both in the Australian context (for the second edition of the national framework for prevention of violence against women, Change the Story (reference 4)). It has also been reviewed in the international context, especially for the United Kingdom Government-funded What Works to Prevent Violence against Women program (referred to here as ‘What Works’), which produced a Rigorous Global Evidence Review of Interventions to Prevent Violence against women and Girls (reference 1), and Effective Design and Implementation Elements in Interventions to Prevent Violence against Women (reference 10) - both published in 2020, drawing on and adding to earlier comprehensive and systematic reviews (reference 10, reference 19). This review did not attempt to replicate the search and analysis processes of these earlier reviews, and instead analysed their findings in the light of the objectives and questions for this research, which were supplemented by primary research and evaluations emerging since those reviews were published.

Assumptions and limitations

By applying the methodology outlined above, the review captured a large part of the literature to guide an exploration and analysis of the review questions, however relevant studies may have been missed.

Beyond the What Works and other ‘whole-of-prevention-field’ reviews referred to above, other rigorous, as well as systematic reviews have focused on specific prevention settings (such as workplaces or education), strategies (such as campaigns or community mobilisation) or population groups (such as adolescents) and include outcome as well as impact evaluations. These have been referred to where relevant, in terms of impact findings generalisable to a place-based, multi-component model, but not investigated in depth.

The upcoming ANROWS umbrella review of prevention interventions in high-income countries (reference 6) will complement the findings presented here, as well as provide more detailed analysis of the evidence-base around outcome (as opposed to impact-only) results of evaluations in such contexts.

A focus in source material on men’s physical and sexual intimate partner violence, and non-partner sexual violence, against women

Most of the source documents, such as the What Works rigorous global evidence review (reference 1) referred to above (and the systematic reviews that preceded and informed it (reference 3, reference 19, reference 38)), define impact in terms of statistically significant reductions in men’s perpetration or women’s victimisation of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (intimate partner violence) or non-partner sexual violence (NPSV). That review acknowledges the limitations of relying on such a determination of intervention effectiveness (footnote 4): it did not include emotional, economic or other types of violence, nor, for example, any violence perpetrated within same-sex partnerships. It also did not include qualitative studies on reductions in perpetration/victimisation, nor quantitative evaluations measuring other types of ‘impact’, such as attitudinal or other changes that were not perpetration/victimisation.

As many of the findings on reductions in violence against women perpetration/victimisation presented in this review rely on What Works and the reviews that preceded it, those limitations also apply here. However, we attempt to redress these limitations by bringing in other sources of evidence and analysis to provide a more nuanced understanding of impact and the conditions, factors and processes that influence impact on broader forms of violence against women, and on the drivers of such violence.

The need for attentiveness when assessing transferability of findings across contexts

The evaluations analysed in existing reviews and discussed here cover interventions from low-, middle- and high-income countries, and often from contexts that vary significantly from Victoria’s in terms of existing prevalence rates, norms around gender roles, and the extent of state and institutional support in creating an enabling environment for change. For example, the review found only three multi-component prevention program evaluations where impact was demonstrated on rates of violence against women at the population-level. Of these, two were designed, implemented and evaluated in Uganda, and one in Ghana.

There is undoubtedly a great deal to learn from such interventions, but caution has been exercised when drawing conclusions about their applicability in a Victorian context. The applicability of interventions will vary across different cultural, social, and political settings, and their effectiveness in, and timeframes for, reducing violence will likely vary depending on the starting rates of 12-month prevalence, and the context-specific factors driving it. The lessons learned from these interventions for the saturation model itself will therefore need to be analysed within the context of Australia's political, social and structural landscape to determine their relevance and potential for adaptation.

Limited evaluation of long-term impacts

Assessment of impact on perpetration/victimisation in the evaluations reviewed here relied upon empirical methodologies that seek, as far as possible in social research, to ensure measured results can be attributed to the intervention, or at least that the intervention can be said to have measurably contributed to the results (footnote 5). In the vast majority of cases, such methodologies have relied on relatively short measurement timeframes that minimise the possibility of other variables affecting incidence of violence within control or treatment populations. They generally measure the difference in men’s perpetration and women’s victimisation at the end, compared to the start, and compared to a control group or groups. Only a small number of interventions have been subject to longitudinal evaluation that follows up with the same participants at later periods to quantitatively measures impact and sustainability over time. The added value of long-term measurement and evaluation was not a focus of the evidence reviews upon which this study draws.

There is obviously only a limited possibility of first experiences/perpetrations of violence emerging (or being prevented) within any short-term evaluation period. Yet most of the findings here are limited to results measured over such a short timeframe; meaning evidence is also limited on the impact these interventions might have on new incidents of violence emerging (or being prevented) beyond their program timeframes.

To fully understand whether an intervention is preventing violence before it occurs, a longer evaluation timeframe is needed. Such longitudinal research would enable, in the intimate partner violence example, an understanding of what happens as participants’ relationships evolve, or as they enter new ones, as a result of an earlier or ongoing intervention. The lack of evaluations that capture this is a limitation of the current review, and indeed currently hampers a broader understanding of how to effectively prevent violence against women.

Return to the top of this page

Footnotes

While not the focus here, a forthcoming ANROWS report reviews interventions in high-income countries that include those demonstrating broader outcomes on drivers and reinforcing factors of violence against women (and proxy indicators).

No major review of prevention interventions conducted over the past decade has surfaced evidence of whole-of-settings based approaches that are as extensive as Victoria’s.

There have been a number of meta-reviews of evaluations employing rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental methods, over the past decade - discussed further under Methodology.

The review also included, to a limited extent, impact on child and youth peer violence – as this was an objective in a handful of the What Works programs.

Most evaluations also include qualitative components that also provide nuance around the nature of the intervention’s influence and the experiences of participants, but the focus here is on the (quantitative) methodological components measuring impact on victimisation/perpetration.